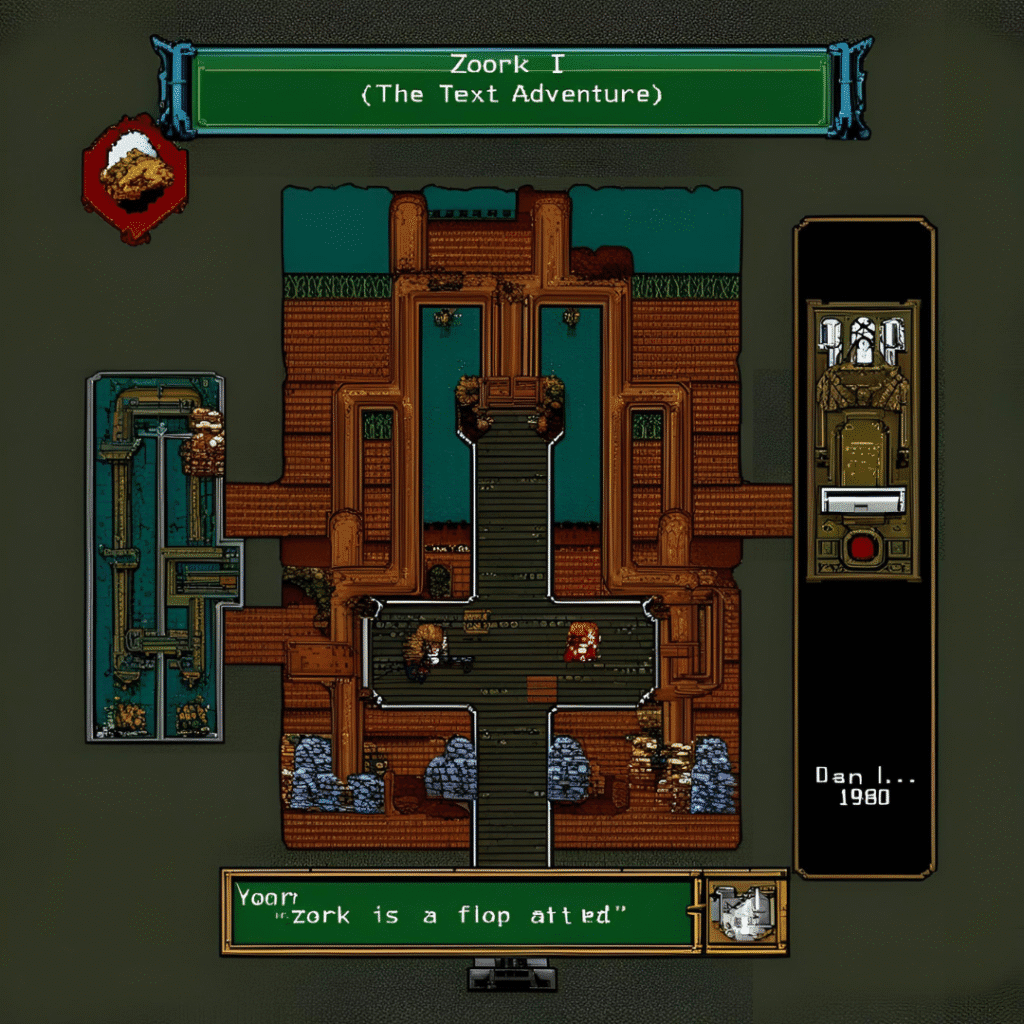

Zork I (1980) – The Text Adventure That Lit Up Imaginations

In the early days of personal computers, when screens showed nothing but glowing letters and floppy disks were the height of storage technology, one game stood out not because of visuals, but because of how it spoke to the player’s imagination. That game was Zork I: The Great Underground Empire — a pure text adventure released in 1980, which would go on to become a cornerstone of interactive storytelling in gaming history.

A Game Without Graphics, but With a Whole World

Zork I had no pictures. No music. Not even colors. Just plain white text on a black background. Yet, for thousands of players in the 1980s, it was more immersive than most modern 3D games today. Why? Because Zork didn’t show you a world — it described one, and let your own mind paint the picture.

You didn’t see the dark forest or the underground maze, but you could feel them as the game described each area in detail. “You are standing in an open field west of a white house,” it might begin — and from there, your journey into a vast underground kingdom would begin.

MIT Origins and the Birth of Infocom

Zork wasn’t built in a big studio or by a corporation. It started as a side project by a group of MIT students — Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling. Influenced by an earlier game called Colossal Cave Adventure, they set out to make something smarter, funnier, and more elaborate.

Originally developed for a mainframe computer in 1977, Zork quickly gained a following among computer enthusiasts. To bring it to the growing number of home computer users, the developers formed a company called Infocom. In 1980, they released the first part of Zork for personal computers, naming it Zork I because it was only a fraction of the full version.

How Zork I Played

Zork I was all about typing — you typed what you wanted to do, and the game responded. Commands like:

go northopen doortake swordread leaflet

The game would respond with detailed text describing what happened. Sometimes you’d discover treasure. Other times, you’d end up in a trap or be eaten by a monster.

The game was full of exploration. You could move from room to room, solve puzzles, collect treasures, and try to survive the dangers lurking in the shadows. Every choice mattered, and one wrong move could cost you everything.

The Grue and Other Dangers

If there’s one line that Zork is most famous for, it’s this:

“It is pitch black. You are likely to be eaten by a grue.”

The grue became a legend — an invisible monster that lived in the dark. If you wandered into a dark area without a light source like a lantern, you’d quickly become its next meal. This was both a clever mechanic (encouraging players to manage their inventory wisely) and a source of fear. The grue didn’t need graphics — the idea of it was terrifying enough.

Other memorable challenges included a sneaky thief who could steal your items at random, mazes that looped endlessly, and doors that only opened with just the right combination of items and actions.

Puzzles That Tested Your Brain

Zork I was not easy. It was designed to challenge your logic, memory, and patience. Some puzzles were straightforward, like unlocking a gate with the right key. Others were more complex, requiring you to gather clues from different locations and think creatively.

There were no hints or guides built into the game. If you got stuck, you had to figure it out on your own — or talk to friends who were also playing. In a way, Zork created its own small community, where players swapped maps, solutions, and secret tips.

A Sense of Humor and Clever Writing

What made Zork special wasn’t just the puzzles — it was the personality. The game was filled with clever jokes, sarcastic responses, and playful moments. Try typing something silly like jump or attack yourself, and the game would respond with dry wit.

Zork treated the player with respect — it didn’t dumb things down. But it also had fun with you, often teasing you for making poor choices or encouraging you to think outside the box.

The Trilogy and Zork’s Expansion

Because the original Zork was too large to fit on early floppy disks, it was split into three parts:

- Zork I: The Great Underground Empire (1980)

- Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz (1981)

- Zork III: The Dungeon Master (1982)

Each game added new areas, new puzzles, and a deeper look into the mysterious underground world. Together, the trilogy told a full story — one of discovery, danger, and triumph.

Legacy and Influence

Zork I is often seen as the grandfather of narrative games. Without any visuals, it proved that storytelling and player choice could be the most powerful parts of a game. It directly influenced the development of later adventure titles like King’s Quest, Monkey Island, and Myst.

Even now, the influence of Zork can be seen in games like Disco Elysium, Undertale, and text-based indie titles. Many modern developers look back at Zork and see the purity of design: a game that asks nothing more than your attention, your imagination, and your willingness to explore.

You Can Still Play It Today

The beauty of Zork is that it has aged remarkably well. Since it’s all text, it doesn’t look outdated — and the puzzles are just as challenging now as they were in 1980. In fact, you can play Zork I today in your web browser, completely free, thanks to online archives and emulator tools.

For those who want a taste of the early days of gaming — when story, logic, and exploration were the main attraction — Zork is the perfect time machine.

Final Thoughts

Zork I isn’t just a game — it’s a piece of digital literature. It showed the world that games could be more than points and lives. They could be adventures, driven by curiosity and shaped by the player’s decisions.

In a world now filled with ray tracing, VR, and AI companions, it’s refreshing to go back to a game where all you need is a keyboard and your imagination. Zork I remains a classic not because of nostalgia, but because its core idea — that stories can be interactive — is timeless.

If you’ve never played it, you’re missing out on a key chapter in gaming history. Just remember: don’t go into the dark without a lantern. The Grue is still waiting.